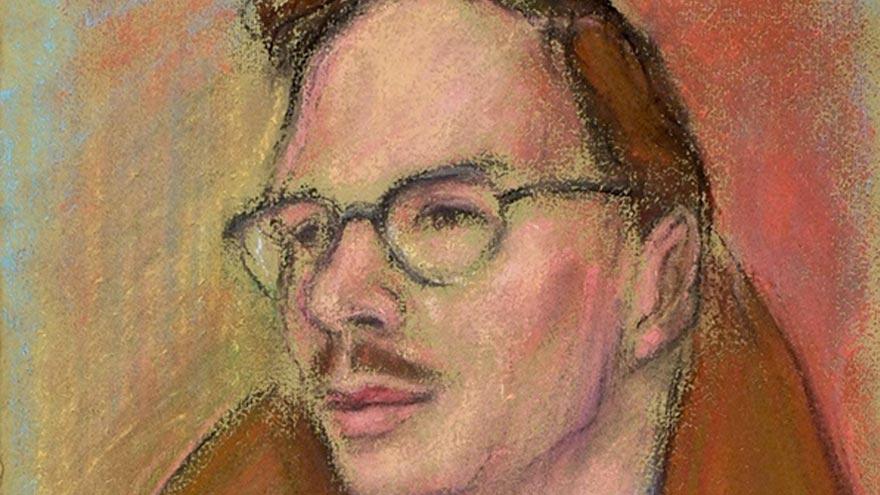

Born: 11 November, 1919, in Blairgowrie, Perthshire

Died: 9 March, 2002, in an Edinburgh nursing home, aged 82

GENERALLY acknowledged as the father of the Scottish folk revival, Hamish Henderson, poet, cultural and political activist, singer-songwriter and folklorist, received his initiation into folk studies literally at his mother’s knee.

As he once recalled: “My mother could sing in Gaelic, Scots and French – French because she had been a nurse in the First World War. One of my earliest memories is of her marching through the house singing the Marseillaise. At the age of seven, I asked her about a song she was singing. We had a book of songs in the house. I asked her where that song was in the book. She said: ‘Some of the songs we sing are not in books.’ That started me off as a folklorist and collector.”

Educated as a scholarship pupil at Dulwich College in London and at Cambridge University, where he studied languages (and spoke in debates in defence of the Spanish Republic), Henderson became a “temporary honorary research fellow” at the newly-founded School of Scottish Studies at Edinburgh University in 1951. His work was championed by the renowned collector Calum MacLean (brother of the poet Sorley), and, in 1954, he was offered a permanent post. A native Gaelic speaker, he often referred to his Perthshire Gaelic proudly, though not without irony, as “tinker Gaelic”.

Prior to his university post, Henderson had acted as a “native guide” to the American folklorist and ethnomusicologist, Alan Lomax, on his visit to Scotland in 1951. In his collected essays, Alias MacAlias (1992), Henderson was to pinpoint this visit as the beginning of the folk revival. But Henderson had already begun to write and collect, and had published Ballads of World War II, a bawdy and vituperative collection of soldiers’ songs, which included some of his own very fine war-time compositions, most notably Ballad of the D-Day Dodgers and Highland Division’s Farewell to Sicily.

In order to evade the censor, it was published “privately” under the auspices of the fictitious “Lili Marlene Club (Glasgow)”, but the book earned him the self-righteous wrath of Lord Reith and associates at the BBC, and he was prevented from making a series of programmes on ballad-making. In fact, he was kept off state radio for ten years because of this publication and because (as an ex-intelligence officer) he had been “ranting red revolution”, as he once put it.

Ironically, sweet revenge was to be his when he publicly turned down an OBE award in 1983 in protest at the Thatcher government’s nuclear arms policy and was, as a result, voted Scot of the Year by listeners to Radio Scotland.

A life-long socialist, Henderson introduced the name of Antonio Gramsci to the Scottish Left (as well as to Hugh MacDiarmid). Described by Eric Hobsbawm as “probably the most original communist thinker of the 20th century in Western Europe”, Gramsci’s influence on Henderson was profound, one of his favourite quotations from the Italian philosopher being: “That which distinguishes folksong in the framework of a nation and its culture is neither the artistic fact nor the historic origin; it is a separate and distinct way of perceiving life and the world, as opposed to that of ‘official’ society.”

Henderson first heard of Gramsci from the mainly communist Italian Partisans, to whom he was attached during the Italian campaign in the Second World War. He was sent the first edition of Gramsci’s Lettere dal Carcere when it appeared in 1947, and he set about translating it. Prison Letters did not, however, make it into print until 1974, when the translation first appeared in two special editions of the New Edinburgh Review, and subsequently in book form in 1988.

Henderson’s war experiences, in the Desert campaign, in Sicily and Italy (evocatively captured in his personal documentary for BBC Scotland, The Dead, the Innocent in 1980), also inspired his Elegies for the Dead in Cyrenaica (1948), a book of poems for which he received the Somerset Maugham Award, as well as the following note of praise – and warning – from the eminent historian EP Thompson: “You must never let yourself … be driven into the arms of the ‘culture boys’ who ‘appreciate’ pretentiousness and posturing. They would kill your writing, because you, more than any other poet I know, are an instrument through which thousands of others can become articulate. And you must not forget that your songs and ballads are not trivialities – they are quite as important as the Elegies.”

In fact, although he was a very fine poet (and arguably one of the most significant poetic voices of the Second World War), it was the songs and the ballads that were to attract him both as writer and collector; and Thompson’s description of him as “an instrument through which thousands of others can become articulate” proved genuinely prophetic.

In the words of the singer/song-writer Adam McNaughton (writing in Chapman magazine in 1985): “Three strands are distinguishable in the Scottish folksong revival: the academic, the club/festival movement and the traditional. Perhaps the only person who has striven to intertwine the three has been Dr Henderson … Henderson’s collecting style is obvious on listening to any of his recordings. He is never the fly on the wall, trying to efface himself altogether. The collecting occasion is a ceilidh in which he is sharing and his voice rings out in choruses or in responsive laughter. Perhaps a more controversial aspect is his now well-known carrying of songs from one singer to another, who in his opinion could make good use of it. Henderson wastes no anxiety on ‘intruding’ with a tape-recorder into the oral tradition. The last thing he wishes is to record museum pieces; he wants a tradition that is fermenting and creative … Hamish Henderson has always valued and encouraged young singers and story-tellers within the tradition.”

Check out his original modern abstract art for sale.

Henderson lived for months at a time with the travelling people of Scotland, collecting songs, classical ballads and stories which had been passed along “the carrying stream”, the travellers having a strong oral tradition, overlooked or ignored (sometimes for purely snobbish reasons) by previous collectors. His work in this area is often regarded as his greatest achievement. He showed the world, particularly the academic world, that Scottish traditional culture was still vigorous and fermenting, and then he went one step further: he brought the travellers’ wealth of oral culture to the public’s attention.

At the People’s Festival Ceilidhs in Edinburgh in the early Fifties, he provided the first public platforms bringing together traditional and revivalist singers. He supported the new folksong clubs (starting, in particular, the Edinburgh University Folk Song Society along with Stuart MacGregor), and became a stalwart of the Traditional Music and Song Association, acting as its president until 1983.

Henderson was particularly proud of his discovery of Jeannie Robertson, once described by AL Lloyd as “a singer, sweet and heroic”. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say that he was prouder of having “discovered” and promoted Jeannie Robertson than of any other achievement. Like many of the travellers (and other tradition bearers such as the Border shepherd, Willie Scott), Jeannie became a close friend. (Henderson’s return to the north-east, where he did much of his initial collecting, was ably captured in Grampian Television’s 1992 Journey to a Kingdom , directed by Timothy Neat). In later years, looking back, Henderson often spoke of his discovery of Jeannie in terms of the “justification” of his life’s work.

His contribution to the folk revival was, in fact, much greater and further-reaching than this. Working closely with enlightened teachers such as Morris Blythman (“Thurso Berwick”) and Norman Buchan (later the Labour MP), he helped inspire a new generation of singers, including the likes of Jean Redpath, Jimmie Macgregor and Josh McCrae. At the School of Scottish Studies he operated a covert “open door” policy, giving many vital access to materials though they were not matriculated students, and he went on to inspire other revivalist singers, among them Dick Gaughan.

Many of his own songs have passed into the tradition, including, perhaps most notably, The Freedom Come All Ye, which has now achieved a status akin to that of an unofficial national anthem in some circles, and The John MacLean March. The latter tribute to the Red Clydesider was first sung by Willie Noble at a commemorative meeting organised by Henderson and Morris Blythman under the auspices of the Scotland-USSR Society in Glasgow in 1948. With 2,000 people in attendance, Blythman later described the singing of Henderson’s composition as “the first swallow of the folk revival”.

That the song’s choral phrase “great John MacLean” derives from a poem by Sorley MacLean (Clan MacLean) is but one small instance of the cross-fertilisation which has always taken place in Scotland between “folk” and “literature” – a cross-fertilisation which Henderson not only embodied but also championed. And championed so vociferously in his famous “flyting” with Hugh MacDiarmid in the letters pages of The Scotsman in 1964, where he not only accused the enfant terrible of Scottish letters of “a kind of spiritual apartheid” but also argued that “by denigrating Scots popular poetry now, Mr MacDiarmid is trying to kick away from under his feet one of the ladders on which he rose to greatness”.

The source of the dispute was MacDiarmid’s thrawn dismissal of folk-song sources as “spring-boards for significant work”. Only, in this instance, the Langholm Byspale perhaps more than met his match. While Henderson tirelessly championed MacDiarmid’s own work (and on occasion provided him with more than moral support), he baulked at the great poet’s “arty” attitude to politics and, in particular, his cultural elitism. For at bottom, Henderson was humanitarian in everything he did, and said, and always held the field for the “democratic intellect”. He saw no other way, and his life’s work, his very motivation, could perhaps be best described by that telling phrase of George Elder Davie’s.

As a visiting student in pre-war Nazi Germany, Henderson acted as a courier for an organisation set up by the Society of Friends (the Quakers), “sending on certain communications to their rightful destinations”, the contents of which he never examined. He was, in fact, part of a clandestine network working to help those in danger in the Third Reich and, although ultimately he did not share their pacifist principles, he maintained a deep respect for the Quakers throughout his life. He was followed. He was questioned, but he was never caught out, his excellent German coming in handy (as later would his Italian).

He told me that on one occasion he stood within yards of the Fuehrer as he passed, standing in an open car during one of the interminable Nazi parades. He described the atmosphere as one almost of “sexual hysteria”, with young women (and some not so young) screaming and crying “rather like a Beatles concert”, though he thought the diminutive dictator an “unprepossessing” figure, returning the Nazi salutes with a “foppish” wave.

Henderson crossed from Germany into Holland on 27 August, 1939, a few days before war was declared. He volunteered but was turned down because of his eyesight. Called up the following year, he joined the Pioneer Corps and spent the winter of 1940-41 building defences along the Sussex beaches, working alongside Jewish refugees from Germany (this regiment being the only one which admitted them). In the spring of 1941, he volunteered as an intelligence officer and was soon shipped out to North Africa, holding to the belief that this “was a war that had to be won”, while later dedicating his Elegies “to the dead of both sides”. In the final analysis. he saw all war as “human civil war”.

He was attached to the 8th Army, prior to the invasion of Sicily in June 1943, and his intelligence operations revealed that there were no German troops manning the strategic Sicilian beaches, only autonomous Italian troops who, he suggested, would “melt away into the landscape”, which was exactly what happened. Not only did he personally intercept and arrest the German paratroop commander in Sicily, Major Guenther, but it was under Captain Henderson’s personal supervision that Marshall Graziani, the war minister in Mussolini’s last government, drew up the Italian surrender order on 29 April, 1945, the first major surrender of an Axis army in the West.

After the liberation of Rome on 5 June, 1945, Henderson also paid a visit to the city’s former SS commander, Lieutenant Colonel Kappler, in jail. It was Kappler who, after a Partisan attack in Rome, had been directly responsible for the retaliatory massacre of 335 civilian hostages in the Ardeatine caves on the outskirts of the city in March 1944. The Scottish soldier wanted to see for himself what kind of man could commit such an atrocity. He found him to be “a stiffly correct, rather prosaic German”. Kappler was described by his own men as “an ice cold, ambitious fanatic”, and Henderson always thought of him as “the carrier of a deadly disease”.

On a return visit to Italy in 1950, Henderson was expelled by the right-wing government of the day for speaking on behalf of the Partisans of Peace, and he did not return to the country until the making of The Dead, The Innocent, though he was a frequent visitor thereafter. The singer-songwriter (often referred to fondly and mischievously by Sorley MacLean as “Comrade Captain”) was also a founder member of, and tireless campaigner for, CND and the Anti-Apartheid Movement. His song, The Men of Rivonia (Free Mandela), written to a Spanish Republican tune was, he was told, actually sung on Robben Island when Mandela was imprisoned there. I once witnessed Henderson singing it to (or, more precisely, at) a South African diplomat during an Edinburgh International Folk Festival ceilidh in the early Eighties. The man left early.

Henderson also believed that he was the target of two assassination attempts by people whom he could only assume were MI5/MI6 personnel operating in cahouts with BOSS, the South African security services. This was not something he spoke about lightly or often. He described to me one of these hit-and-run attempts on an Edinburgh street in clear detail.

An Old Labour man and a veteran home-ruler, Henderson was also involved in many and various post-war home-rule campaigns and organisations, as well as the John MacLean Society. He also played his part in the setting up of the short-lived Scottish Labour Party of the Seventies.

Although he spoke often of his mother, he rarely spoke of his father or his father’s family. He told me that he was, in fact, an illegitimate son of a cousin to the Dukes of Atholl, and was a direct descendant of Robert II. Bill Shankly’s famous description of Jock Stein as “a man with the blood of Bruce in his veins” was literally true in Henderson’s case. The reason he did not speak publicly about his parentage had nothing to do with any sense of shame about being illegitimate. He simply did not think that any public knowledge of his aristocratic links would benefit him in the work he did.

He was very proud of, and close to, his two daughters, Janet and Christine, and to his German wife, Katzel. But it was no secret to anyone who knew him that Hamish was bisexual and he spoke and wrote openly on such matters long before it was fashionable (or safe) to “come out”. (He also intensely disliked the word “gay”).

He spoke often of his Perthshire childhood, recalling once how, at the age of five, he was evicted along with his mother from their cottage because she could not afford to pay the rent. He knew, first hand as he once put it, “what the Clearances meant”. He was brought up in the Episcopalian tradition, looked upon the Episcopal Church as, historically, “the Scottish church”, and was proud of its links with the Jacobites. He had little or no fondness for Presbyterianism, and often attacked the Church of Scotland for its role in the Clearances.

In some ways there was as much of the Jacobite in him as there was of the Jacobin. He was also a man who did a great many private kindnesses for a myriad of folk. Though never a rich man, he helped many people in financial need over the years, and gave of his time and talent, not least to Scotland’s small literary magazines, generously.

Once, walking with him from the School of Studies in George Square, Edinburgh, to his favourite howff, Sandy Bell’s in Forrest Road, we saw approaching us in Middle Meadow Walk the kenspeckle figure of Father Anthony Ross, then rector of Edinburgh University. Hamish remarked: “Look, here comes Father Anthony. That man’s heart could float a battleship.”

Surely a fitting epitaph for Hamish Henderson himself.